Nina Sanadze: National Gallery of Victoria, survey show

The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Fed Square, Level 3

12 Apr – 4 Aug, 2024 | Free entry

A monument to sculpture. Presenting six works at NGV, Melbourne-based contemporary artist Nina Sanadze looks at the meaning that public statues carry, and how it can change over time, despite their solid materials…

To learn more go to NGV website HERE.

video by Astrid Mulder, 2024

NGV: Exhibition Space 1 and 2

Monuments and movements

Photos by Astrid Mulder, 2024

Being born in the Soviet Union in the late stages of communism, I grew up witnessing the end of many epochal milestones. There was the end of my country, of a regime, of an education system, and even of my family life as I knew it. But endings, however violent, painful and destructive, can also signify new beginnings. Whether these new beginnings are positive or not is a difficult question, but there is always hope. Most of my work traces the end of eras, systems, beliefs, societies, nations and empires. Examining these ruins may offer insight from a retrospective angle, allowing us to glean lessons from history and forge a more promising future.

While journeying through Australia and New Zealand, I’ve come across numerous monuments to Queen Victoria that bear striking resemblance to one another. In a sense, these are reminiscent of the plethora of Soviet monuments that were replicated in every town.

In Monuments and movements I was interested in delving into the concept of endings, exploring the remnants and ruins left behind. To me, the monuments still standing around Melbourne, despite their preservation, already exude an aura of decay and are essentially ruins. Perhaps this is because, akin to classical art, they represent a distant past and belong to an era where people believed they could immortalise themselves through sculpture or assert their power and longevity through such monuments. The timeless beauty associated with classical art, epitomising the inner beauty of the idealised human form, is somewhat fractured in my works as I introduce themes such as imperfection, fragility, decay, transience, destruction, violence and mortality.

Creating Monuments and movements was a process of experimentation and refinement, involving numerous variations and prototypes. It took me a year to arrive at the final streamlined forms you see today. These sculptures needed to be easily folded and unfolded, yet sturdy enough for mobility through the city. The initial life-sized prototype depicting a figure on horseback (Edward VII) was crafted from wood and painted with subtle brushstrokes in various colours. Testing it near monuments revealed a challenge: the sculpture frequently toppled in the wind, with the wooden panels acting like sails.

I frequently engage in performative acts while carrying my sculptures in public spaces. My work originates from the infrastructure of public space before transitioning to the gallery, so I derive pleasure from reintroducing it to public settings in a playful and thought-provoking manner.

Walking with these sculptures along St Kilda Road, opposite the NGV, and activating them around the referenced monuments was a crucial aspect of this work. When the sculptures are pushed, they produce a resonant rattling noise against the asphalt, evoking the sound of horses running or trains moving. Engaging in a performance like this truly accentuates the oddity of the situation. I take pleasure in creating this mild disruption in a public space while maintaining a serious demeanour. It’s not intended as a protest or to cause discomfort or obstruction to people; rather, it’s more of a thought-provoking act, prompting observers to ponder, ‘Oh, that’s intriguing, what is this?’ Despite its impracticality and peculiarity, it still embodies the essence of artwork and arouses curiosity. Additionally, it directs attention to the monuments themselves, as I sometimes position the sculptures in front of them, aligning their silhouettes precisely. It’s a playful endeavour and a subtle means of reshaping perceptions about monuments, executed with a touch of poetry and symbolism.

The Constructivist minimal aesthetic in this work draws inspiration from Soviet agitprop trains, establishing parallels between Soviet propaganda and colonial monuments. Agitprop trains symbolised an idealistic vision for early communists, acting as an educational vehicle that travelled through remote regions. They delivered ideologically charged films, theatre and art by prominent Constructivist artists, propagandising to those receptive to change but unaware of the darker aspects of the glorified new ideology’s inherent violence.

My background in designing theatre and stage costumes has a discernible influence on my work, which often possesses a theatrical or cinematographic quality. There’s a deliberate embrace of the fakeness of materials and an intention for observation, contemplation and scene-setting rather than aiming for absolute realism or permanence. I hold a profound appreciation for the ephemeral beauty intrinsic to theatre as it resonates deeply with the transience of the human condition.

Bollard city

From 2017 to 2019 I crafted numerous artworks centred around anti-terrorist bollards and barricades. Given the modular nature of my work, these pieces often evolved based on the setting and context, serving as a practice of questioning and testing new propositions.

Bollard city was my first major body of work. It was sparked by my sheer shock and a profound sense of urgency following an encounter with the hundreds of bollards erected in Melbourne in the aftermath of a car attack in 2017 that killed six people in Bourke Street. The sight of the bollards dredged up memories of the civil war I experienced as a teenager, stirring a deep-seated fear and poignant sense of foreboding regarding the loss of safety and innocence I once felt in Australia. It has never been the same since then.

I began by placing text-based works, stencils and paste-ups directly on the actual bollards in the city. This was followed by sculpting numerous realistic replicas of bollards and creating various installations in galleries and temporary public art exhibits, such as Bollard up the tree. I also staged a dance performance as well as a playful walk around the city carrying a lightweight yet convincing bollard with the aim of reintroducing these objects as sculptures and performance props.

Through a continuous practice of questioning and reconfiguring my sculptures, new revelations unfold. Storing these bollards in and around my home, I came to recognise their deeper significance in this domestic and intimate setting. When placed within a home, bollards symbolise our inner and concealed fears, which we often disguise, although clumsily, as displays of strength. This realisation prompted me to create multiple works exploring the seemingly absurd contrast of defensive public architecture merging with the domestic landscape, echoing themes found in the Head under the bed installation. These artworks aim to capture the internalisation of fear and violence in our psyche, illustrating how such external elements infiltrate our inner lives and private spaces daily.

While extremely different in their form and aesthetic, the connection between Bollard city and Apotheosis becomes apparent when placed in the same room. Both installations represent barriers or barricades, although in vastly different ways. Despite these differences, both monuments and bollards form structures found in public spaces, reflecting on the psychology of its citizens, the passage of time, and the ever-changing political landscape. They serve as tangible symbols of societal values, fears and aspirations, inviting viewers to contemplate the intersection of architecture, public space, politics and human experience.

Indeed, the connection between Bollard city and Apotheosis carries echoes of the Russian revolutionary anarchist Mikhail Bakunin’s idealistic, paradoxical idea in 1849, during the socialist insurgency in Dresden, of placing paintings from the National Museum’s collection in front of military barricades. He speculated that Prussian soldiers would hesitate to destroy the works and thus be deterred from advancing past the blockades. Bakunin’s plan was never enacted; however, this historical anecdote underscores the complex relationship between art, politics and resistance.

Bakunin’s proposal reflects the belief in the power of art to transcend boundaries and influence human behaviour, even in times of a violent conflict. Similarly, Apotheosis and Bollard city provoke contemplation on the role of public monuments and structures in shaping societal dynamics and confronting political realities.

(Text from the NGV Broadsheet Publication accompanying the exhibition Nina Sanadze. Written by the artist)

NGV: Exhibition Space 2

Apotheosis

Photos by Astrid Mulder, 2024

Apotheosis is created from the original remnants of the studio archive of Valentin Topuridze, a prominent Soviet monumental sculptor. My dad went to school with Topuridze’s son, Archil Topuridze, who was also a sculptor. Our families were neighbours for three generations and became friends. I grew up as the closest friend of Valentin Topuridze’s granddaughter, Maka Topuridze, also a talented artist.

When I returned to Georgia in 2006, my first visit since leaving the country in 1992, I returned to create a film about my late father, Eduard Sanadze, who was a renowned musician in Georgia as well as an amateur artist. During this trip, I uncovered a surprising connection: as a young man, my dad had occasionally modelled for Valentin Topuridze. It dawned on me that his likeness might be captured in some of the sculpture models in Apotheosis. Archil then revealed to me that they possessed sculptures of my dad’s foot and hand cast.

Valentin Topuridze’s archive was preserved after his studio was dismantled. In a countryside hut, the sculptures were packed into numerous hessian bags, filling the room. Remarkably, the first bag I opened contained the cast of my father’s hand, sitting prominently on top – an extraordinary coincidence. The images of sculptures packed away in those bags lingered in my mind, and in 2018 when I had the opportunity to exhibit at the Tbilisi Triennial, I approached the Topuridze family to borrow some sculptures for the installation.

The installation process for the Tbilisi Triennial was an intensely emotional experience for me, often leaving me unable to hold back tears. There was something so naked and revealing about the sculptures. I found them both beautiful and broken, embodying so much pain and history, yet also intimately familiar to me from childhood.

Recognising the resurgence of Soviet totalitarian ideology and Stalinism in Russia, the initial iteration of Apotheosis at the Tbilisi Triennial was titled ‘100 years after, 30 years on’ and took the shape of a barricade. These resurrected, discarded Soviet sculptures marked thirty years since they were pulled down. It also marked a century since Tsarist monuments had been earlier dismantled (as witnessed in the Head under the bed installation).

(Text from the NGV Broadsheet Publication accompanying the exhibition Nina Sanadze. Written by the artist)

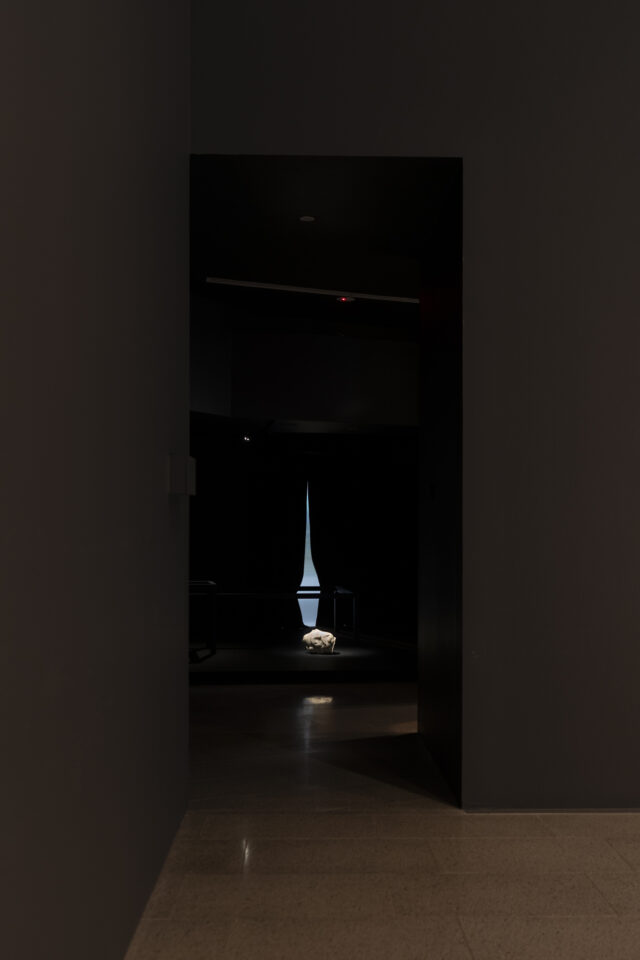

NGV: Exhibition Space 3

Call to peace, anatomy of the dream

Photos by Astrid Mulder, 2024

I think it’s poignant to recall my initial idea, my ‘dream’, for the installation Call to peace, anatomy of the dream. I still have the original sketch depicting an assembly of approximately fifteen casts of full female figures, similar to the luminous blue sculpture in the installation, each bearing subtle distinctions and rendered in diverse materials and hues. This hopeful vision would have embodied a more positive manifestation of Call to peace, anatomy of the dream, evoking a dance floor adorned with female figures donning billowing, colourful dresses. The main component or motif of this work is Valetin’s interpretation of the iconic Nike of Samothrace sculpture. Considering the current installation, it’s difficult to envision this big, bright and life-affirming vision, but indeed, that was my original dream for this work.

Throughout the painstaking process of crafting the clay sculpture and mould, and the creation of the first and only full cast (the blue figure) spanning 2021–22, the ‘dream’ underwent a metamorphosis of translation from its initial idealistic vision in my mind to its realisation as tangible objects. This transformative process, revealing the inherent challenge of bridging the chasm between a dream or idea and reality, embodies the essence of the work – the anatomy of our hopes and dreams.

These colourful ‘dreams’ of peace, when confronted with reality, poignantly manifested as both shattered hopes and resilience. The installation delineates the journey of creation, contemplation and daring to dream on a grand scale, all while facing the insurmountable barrier of realising the dream exactly as envisioned. Coming to terms with my limitations in making the original dream happen, as well as gratefully acknowledging and recognising the beauty of unplanned discoveries, surprises and lessons that the creative studio process produced, I gathered every part of this making and failing journey as an ‘anatomy of the dream’.

The installation includes the original unfired clay model, my first Call to peace, which I sculpted in late 2021. The model was damaged naturally though the process of mould making and transportation. I call it a ‘living sculpture’ as it is in a constant state of change, transformation, and dying as water evaporates from clay and it turns to dust.

The unused armatures signal my thinking and planning to make many more versions of Call to peace sculptures. For me, these also visually connect to my Monuments and movements work referencing Constructivist aesthetics. I was recently compelled to use one of these armatures to grow and change this original installation. In response to the events of 7 October 2023, I sculpted a new Call to peace as I have a personal connection to this event, as I do with all works in this installation.

(Text from the NGV Broadsheet Publication accompanying the exhibition Nina Sanadze. Written by the artist)

NGV: Exhibition Space 4

Head under the bed

Photos by Astrid Mulder, 2024

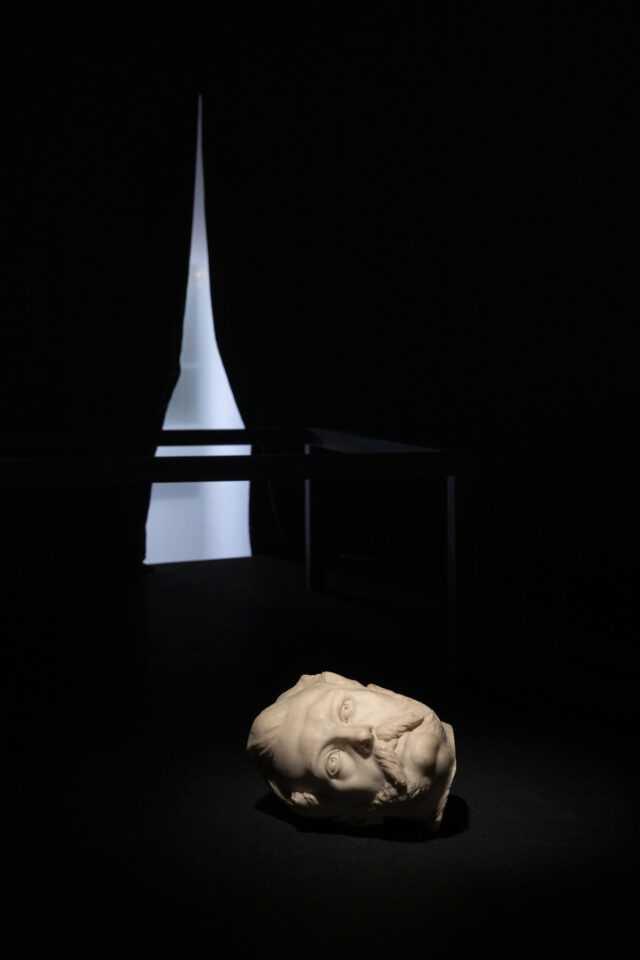

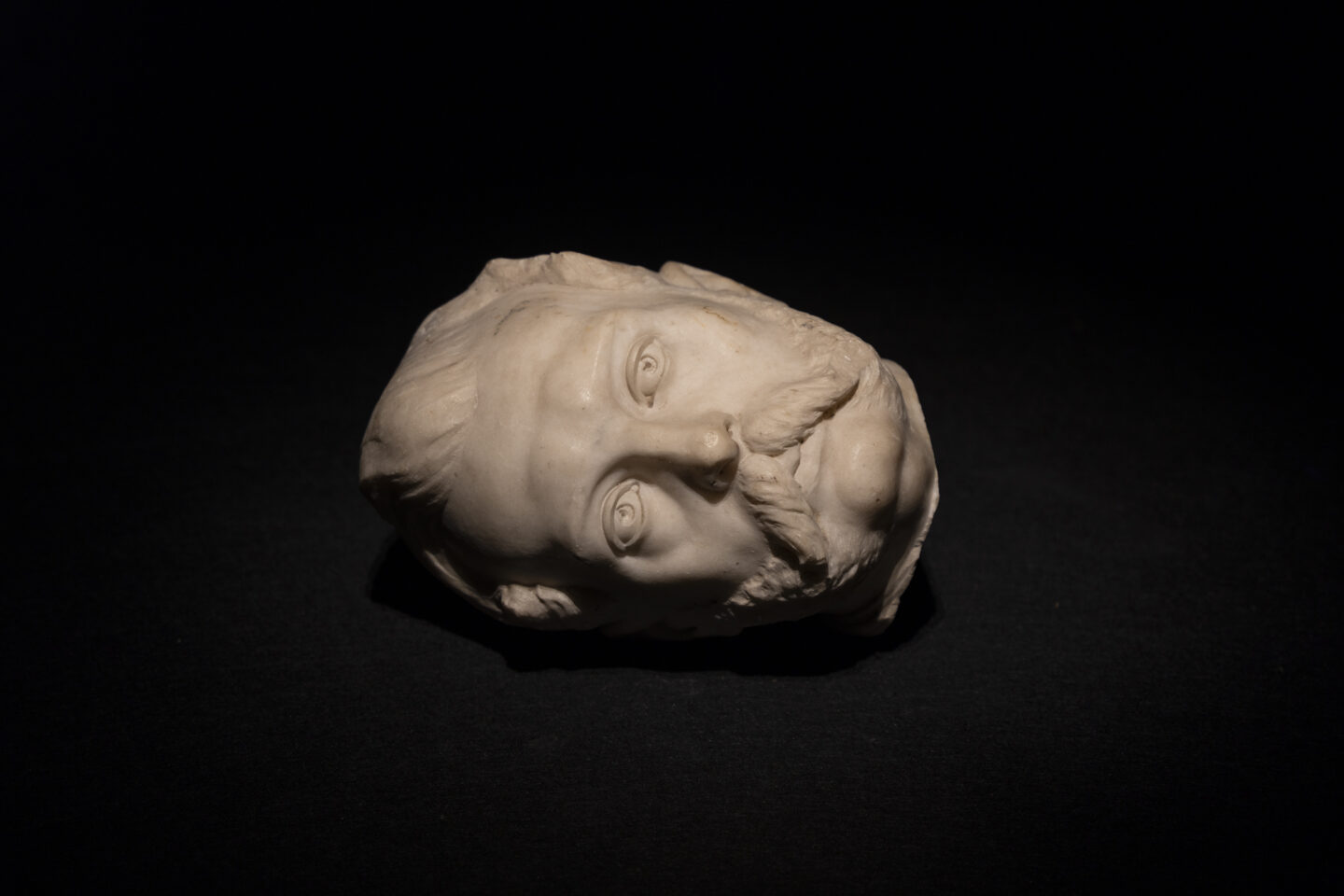

Head under the bed is based on the bedroom of Valentin Topuridze’s great-granddaughter. During my visit in 2018 to Tbilisi, Georgia, to install my work for the Tbilisi Triennial, I stayed for a week with the Topuridze family in this very bedroom.

By the end of the week the original marble sculpture of Russian Emperor Alexander II was brought out by family members from some secret corner of the house – a surprise revelation for me. I captured a photo of the scene that left a profound impression on me. The banal setting of the bedroom stood in incongruous, shocking contrast with everything that this sculpture represented.

Seemingly alien in this domestic setting, the beheaded sculpture viscerally encapsulated grand royal history with its violent ending at the hands of communists. Yet, I thought, it also belonged there in a way that echoed the communist credo of ‘art belongs to the people’.

(Text from the NGV Broadsheet Publication accompanying the exhibition Nina Sanadze. Written by the artist)

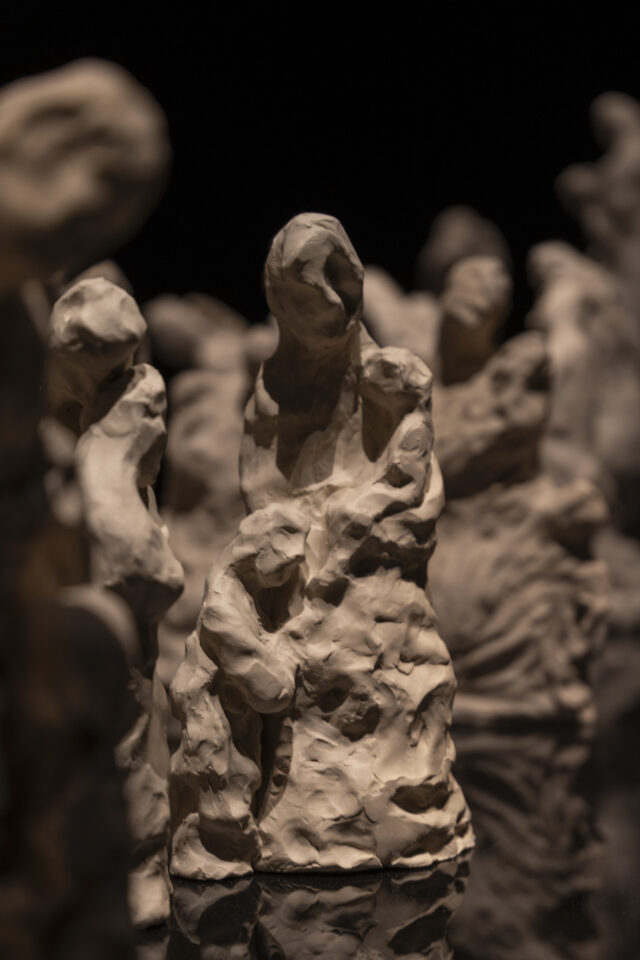

NGV: Space 5

Hana and child

Photos by Astrid Mulder, 2024

The idea for Hana and child came to me after watching the haunting documentary Einsatzgruppen: The Nazi Death Squads on Netflix. It featured a distressing image on its cover – a well-known photograph by Jerzy Tomaszewski captured in 1942 in Ivanhorod, Ukraine, during the Holocaust in Eastern Europe. The image portrays a soldier aiming his rifle at close range towards a mother, who is desperately attempting to shield a small child with her body.

Sometimes, images can convey more than words ever can. Growing up with the knowledge that my Jewish great-grandmother, Hana, along with her three children, Misha (14), Efim (12), and Rachel (8), were murdered in similar circumstances, made me realise that this photograph could be a visual representation of them and their fate, encapsulating this chilling history in a single image. Upon further investigation, I discovered that the photograph was taken in close proximity to where Hana lived with her family – it could very well be her captured in that haunting image.

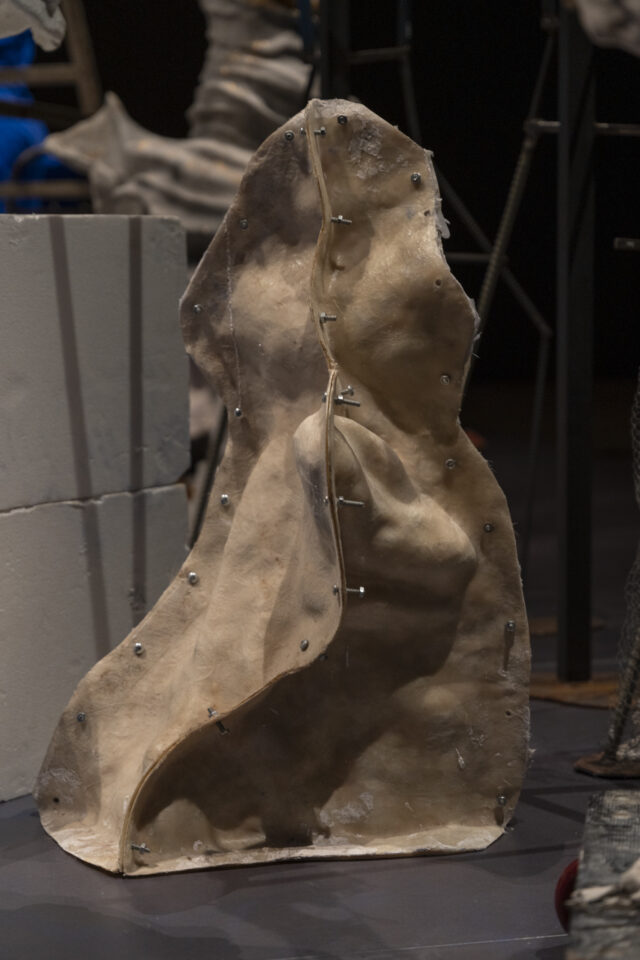

Since then, this photograph has become the anchor point for hundreds of my sculptures, each depicting women and children in a tender embrace during their final moments. I was hoping to convey the overwhelming magnitude of loss and the enduring bond between parent and child. Each sculpture serves as a tribute to Hana and her children, capturing the unimaginable tragedy of their untimely deaths and honouring countless others who suffered similar fates during that dark chapter of history.

Hana and child captures the daily, sometimes repetitive practice of art interwoven with moments of agony. It is imbued with both mundane routine and profound emotion, the ordinary and the extraordinary, evoking a sense of intimacy, tenderness and underlying struggles or grief. While creating this body of work, it felt like I was navigating a recurring thought, meticulously explored and examined over a hundred days. Each sculpture served as a reflection of continuous introspection and emotional involvement, raising the question of whether or not thoughts and feelings can be embodied in physical form.

The malformed shapes, gradually taking on recognisable figures, symbolise more than a sculptural form. Instead, it’s a commitment to exploring a recurring thought that is challenged by questions of duration and discipline: How far can I push this exploration?

My mother became a significant part of this project, assisting me with the more technical aspects. I sculpted and my mother then cut the figures in half to hollow them out before re-joining them again, ready for firing. This process was both painful and healing, as it allowed her to remember her grandmother, whom she never met. One could also say that the hidden inside of each sculpture represents the work of my mother – her hidden labour of love.

At times, hitting a wall, I sensed that I fell short of fully conveying the depth of expression required. While I consistently rejected the notion of replicating the violence depicted in the reference photograph it remains a challenge to say more than what the photo already does.

Despite the boundless stories and emotions behind each sculpture in Hana and child, there was a realisation of the inherent limitations in conveying the depth of human experience through sculpture alone. The photograph that served as a powerful anchor behind every sculpture felt elusive, as if its essence was impossible to fully capture, no matter how many times I attempted to sculpt it. Yet, I persisted. Each subsequent sculpture held the promise of capturing that essence, yet I remained unsure if any truly achieved it. When I assembled all the sculptures together in the gallery, however, the expanse of the installation, the subtle shimmering colours and their humble scale felt fitting, creating an atmosphere that resonated. It reminded me of a clear and shallow shimmering mountain river with its myriad rounded pebbles, each ghostly figure whispering a prayer.

(Text from the NGV Broadsheet Publication accompanying the exhibition Nina Sanadze. Written by the artist)

Brutal Regimes shaped from noble ideas_Nina Sanadze, artist, 48: Q&A | The Australian

Artist Nina Sanadze interrogates dark histories at NGV Australia | The Saturday Paper