Embedded

11.35min film

*To watch the film please email me a request for a private link.

This film was exhibited at the Incinerator Gallery as part of Art for Social Change Award 2021 exhibition.

13 August – 28 November 2021.

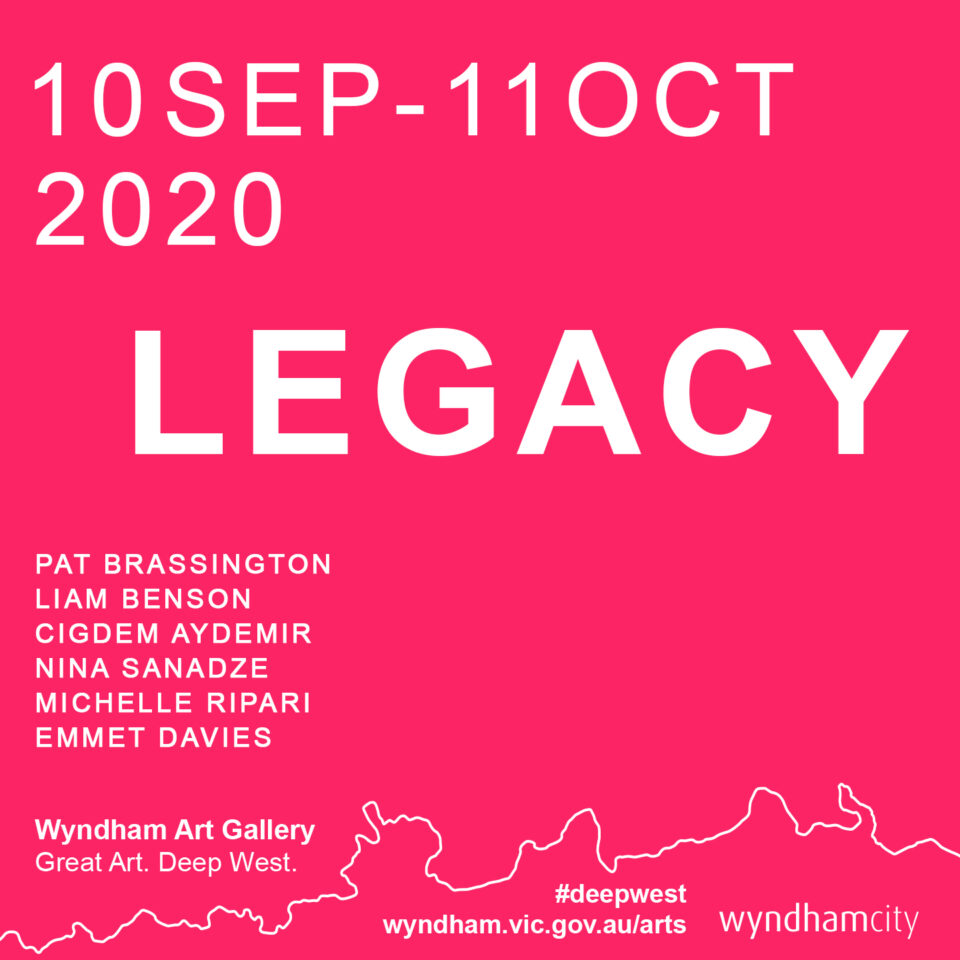

This film was first exhibited and commissioned by Wyndham Art Gallery, 10 September – 11 October 2020.

It was part of the exhibition Legacy curated by Caroline Esbenshade and Megan Evans.

To view the exhibition catalogue, read curator discussion and an essay by Dr Ashley Crawford press on this link:

LEGACY catalogue essay by Dr Ashley Crawford

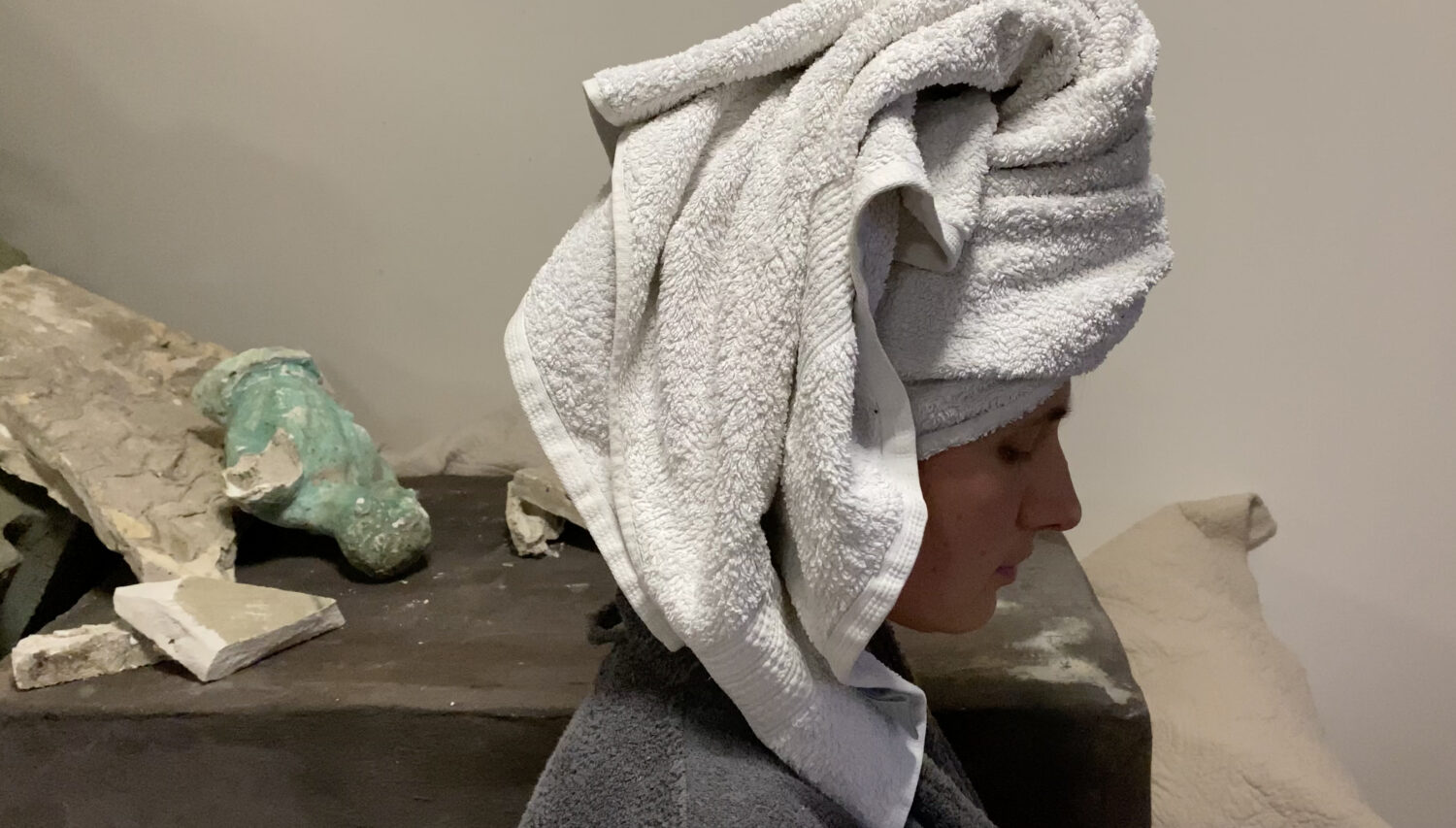

For LEGACY, Sanadze’s planned installation rapidly evolved into the creation of a short film due to the stage 4 restrictions in Melbourne. Emblematic of this time, Embedded is filmed at the artists’ home studio, offering a sensory, meditative exploration of how public, politicised structures intrude into private spaces. In our isolated state we see both a metaphor for current social upheavals playing out on the screen as well as a larger discussion around monuments.

Embedded offers a glimpse into the future through a unique perspective toward the current debate around corrected commemoration. Thirty years after the fall of the Soviet Union, the film examines a decaying studio archive of a prominent sculptor whose monumental works were torn down. It also reveals the Russian Emperor’s marble head, dismantled from a public square 100 years ago by communist authorities.

Within one room, the camera takes us on a compelling journey that explores a space that is at once an archaeologist’s camp, a studio, a history museum, a bedroom, a city square and a home. Bringing these polarised spaces together, expressed through the contrast of sound and imagery, this work questions how the beauty of art and the violent history it embodies operate as two sides of the same coin. What is the legacy of visual forms of violence and propaganda embedded in the collective memory?

News footage of the falling monuments brutally cuts into this quiet, ambiguous space. Universally recognisable and uniformly generic, it is hard to place it in any particular time and country. Timeless through the reiteration of history it speaks to this moment.

Sanadze also occupies the space, dressed in a dressing gown with an open book – the oldest, and the most recognised repository of chronicles, recounting history from a vulnerable personal position.

What is the legacy of visual forms of violence and propaganda embedded in the collective memory, and what’s their impact on the individual?

* * *

Nina Sanadze was born in former Soviet republic of Georgia and now resides in Melbourne.

As a close family friend and neighbor, she grew up amongst models and monumental works in progress, in the studio and garden of a prominent Soviet sculptor Valentin Topuridze (1907-1980). Climbing giant fragments of Lenin’s and Stalin’s heads, noses and hands, the unusual playground-like setting, and the consequent violent fall of his monuments from public places has informed Sanadze’s artistic practice in a fundamental way.

There is still a mixture of shame, confusion, aversion and travesty associated with soviet propaganda art and what it represented. However, working with Topuridze’s surviving archive Sanadze uncovered something altogether surprising. No longer grand and victorious, sculptures appear poignantly small and fragile. Material deterioration through time and neglect reveal their intrinsic artistic beauty. Symbolizing the precariousness of the human condition, both socially and bodily, the sculptures present us with the violent history they incarnate. The combination of this obsolete and frail beauty and the implicit history of terror behind them creates tension and a strong emotional response, conceding our divine, yet flawed and self-destructive humanity.

Having since acquired and transported Topuridze’s archive from Georgia to Australia, Sanadze used it to develop a material language that describes temporal and political memory through various installations. Now, surrounded by the artefacts of Topuridze’s practise in a domestic setting, on the other side of the world, it is a chilling evocation of that childhood and the impetus behind the film Embedded.